30 May 2019

Lead By Example: Why Clear Behavioural Precedent Is Crucial For Motivating Team Members

When faced with a looming project deadline, most project managers have multiple tools at the ready: task tracking, goal setting and the daily morning meeting all contribute to a project that is delivered on time – but can leadership from other domains reveal another piece to the puzzle?

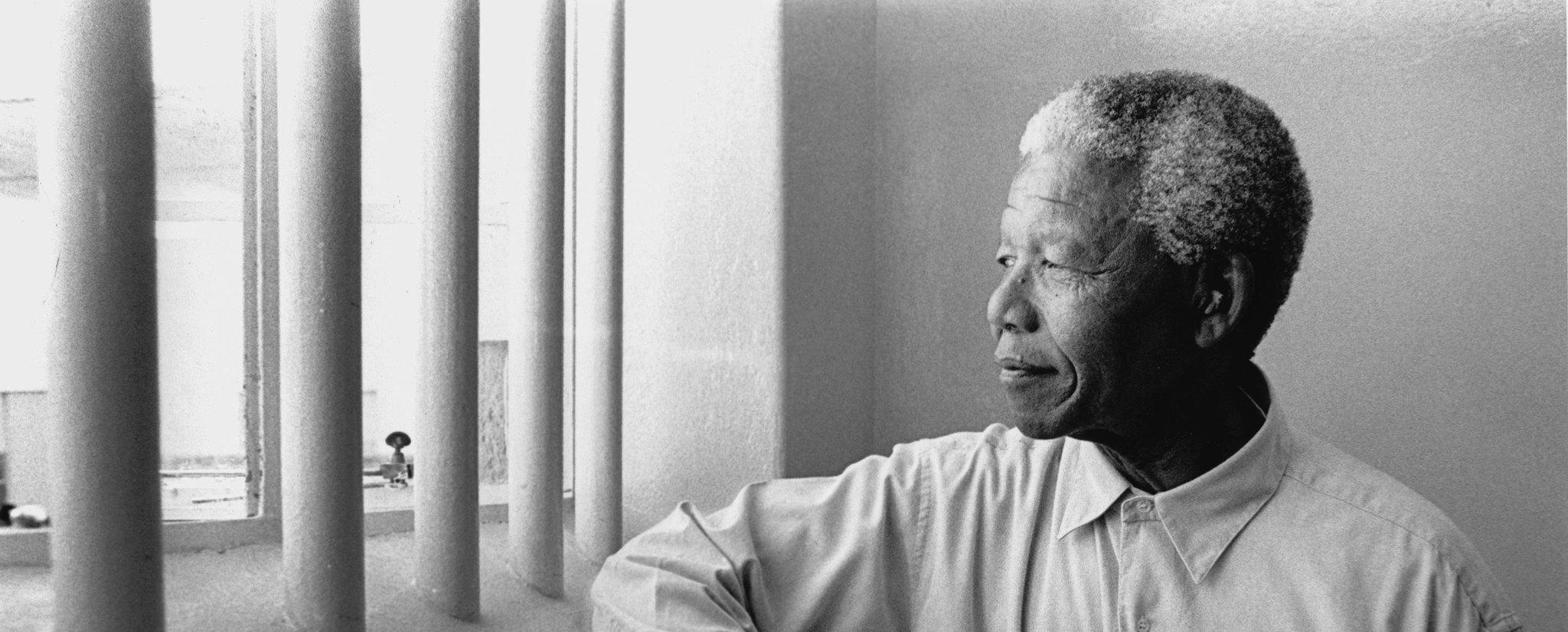

South Africa's first black President Nelson Mandela revisits his prison cell on Robben Island in 1994.

(Jurgen Schadeberg / Getty Images)

Politicians might organize their teams with the right tools and performance targets – but the speeches delivered at each stopover are what really set the tone of the campaign. Similarly, the military General may be following a detailed plan assembled back at base – but his behavioural motivation of the team towards these targets is what really fuels a successful military operation.

For your own project team, this is no different: team members crave for tribe-like leadership, and introducing the right behavioural precedent could be the final ingredient that gets your project over the line.

TEAM MEMBERS FOLLOW THE LAST ONE STANDING

We have all heard of the ‘captain standing by his sinking ship’. But this really conjures up an example of behavioural precedent – not a solution to a project outcome.

Amidst all of the military strategy that took Britain through its greatest threat of all time, Winston Churchill adopted this exact same behaviour: as German forces drew closer, and delivery deadlines drew nearer; this tone of leadership accountability and ‘national unity’ was what would align military and home-based forces to the nation’s ultimate success. If Britain had failed, Winston Churchill would have remained the last one standing.

But the precedent that this set behaviourally for factory workers and military generals from the beginning was the ingredient that allowed Britain to rise (Strock, 2015): successful leaders know when to emulate this trait, and several leaders in the sports domain are attributing successful team outcomes to similar behaviours.

In the case of football manager Jürgen Klopp, we see a similar pattern. According to footballer Mark Lawrenson, this ‘team first’ and sense of top-down responsibility that Klopp instils into his team is what led to the record points tally in a single Premier League season: according to Klopp, ‘enjoying the ride’ as a team is more effective than training towards a binary outcome of ‘win or lose’; and ironically, this collective approach of leadership is what has unlocked the performance needed from his team needed to win.

TAKING ACTION MEANS RUTHLESS GOAL SETTING FROM THE TOP

Returning to the military domain, we see that the behavioural precedent of ‘owning team outcomes’ to create a sense of collective unity is not enough: this also needs to translate to a concrete culture of goal-setting.

For Winston Churchill, this meant combining a captain-like leadership and the sense of collective unity with a culture of concrete goal-setting behind the scenes.

According to United States General Steve Mattis, these qualitative behaviours of ‘establishing outcome accountability’ are only effective if combined with a ‘cultural obsession with goal setting’ and comparing day-to-day progress with the targets of the wider project (Valenti, 2014).

Moreover, recent studies from the National Research Council in Washington DC reveal ‘unit performance factors’ that are introduced deliberately by military leadership to maximize team performance.

For project leaders outside of the military domain, these unit performance factors can be combined with other leadership behaviours to measure team progress more objectively towards a project deadline.

PROGRESS FOLLOWS A LEADER WHO TAKES A STAND

Setting a precedent of responsibility for team outcomes – both practically and behaviorally – is a vital ingredient for any successful military operation. But a closer look at the political challenges that have triggered military action reveals another behavioural precedent that can be necessary to achieve a goal that is much longer-term.

The scale of a military operation might require a long-term strategy of months and years – but the deep and embedded nature of a societal problem such as racial discrimination may mean a battle of a lifetime: in the case of Nelson Mandela, the courage to stand-up to Apartheid in South Africa would require a selfless personal sacrifice – but his choice to adopt this long-term mindset led to an impact that would transform race relations for his country forever.

In the case of athlete Caster Semenya, although the targets and timespans of her profession may differ, the behavioural precedent to learn from her career is the same: although racial discrimination may not present the same barrier as it did under South Africa’s Apartheid before the 1990s, gender bias and sexist discrimination still persist. However, despite battling the debate of testosterone usage and the double standard that still faces female athletes, this battle only helps her resolve by revealing a barrier that she can break-through: in time, her success will set an important platform for battling gender discrimination and attracting female talent into fields that have been traditionally male-dominated.

Although the targets and deadlines of a project with a much shorter lifespan may not require this personal level of sacrifice, the behavioural precedent for a project manager should be the same: although team members should be guided towards incremental milestones to ensure that objective progress can be measured day-to-day – aligning shorter-term projects towards an ‘imagined ideal’ of the future ensures that team are personally invested in the ‘societal mission’ of your project or business model (Papulova, 2014).

LEARNING FROM THE TOP RAISES LEARNERS AT THE BOTTOM

Without doubt, behavioural precedent is instrumental for motivating your team members towards project deadlines at multiple levels: creating a sense of ‘collective unity’ and ownership of team outcomes; behaviorally integrating this accountability, and adopting a wider ‘societal mindset’ all contribute to achieving a project target.

However, a closer look at leaders across the military, political and athletic domains may reveal a common thread:

From the famous home library owned by General Mattis to Winston Churchill’s ‘reading retreats’ (Boitnot, 2018), the humility to acknowledge natural weaknesses and learn from other domains may be the fuel that binds all of these strategies together.