4 June 2017

Bright future in store for Singapore sport

Daniel Gallan (@danielgallan)

In an exclusive interview, CONQA sat down with the Chief of the Singapore Sports Institute to discuss the small nation’s ambitious plan to be recognised not only as a host to the world, but as a force to be reckoned on courts, tracks, fields and in pools around the world.

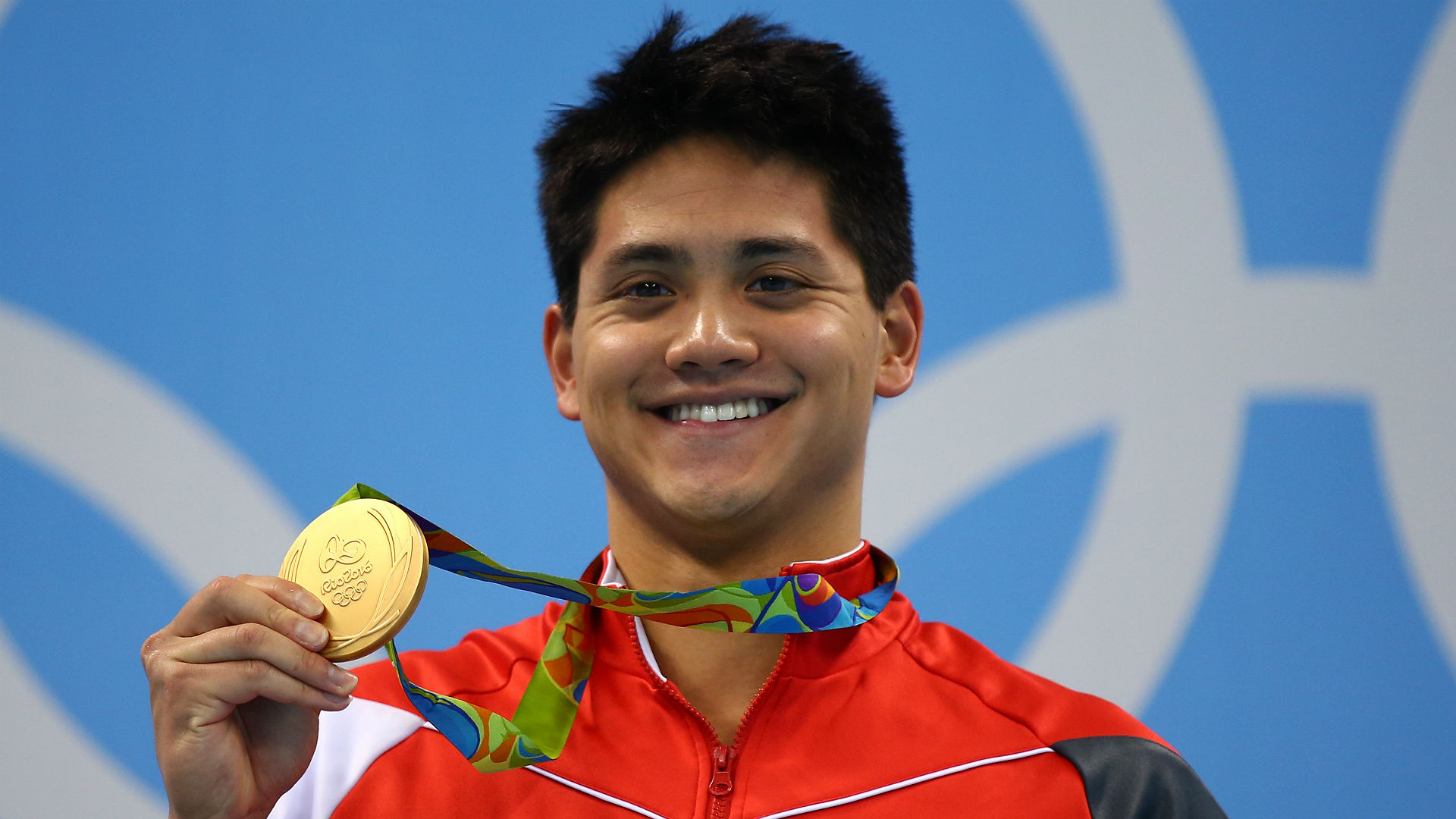

Joseph Schooling is all smiles as he becomes Singapore's first ever Olympic gold medalist in Rio 2016.

Before Joseph Schooling touched the wall of the Olympic pool in Rio de Janeiro in the finals of the 100m butterfly at last year’s Summer Games for a time of 50.39 seconds, his native Singapore had never claimed an Olympic gold medal.

By beating Michael Phelps and Chad le Clos, Schooling changed the sporting identity of the small city-state.

That is the opinion of Toh Boon Yi, Chief of the Singapore Sports Institute (SSI), the man largely responsible for driving the country’s national sports associations, youth high performance centres, government agencies, schools, coaches and athletes towards a single mission to transform Singapore into a sporting force on the world’s stage.

“Joseph’s medal showed our five and a half million citizens that we are capable of athletic greatness,” Toh says from his headquarters in Singapore. “It’s not just the sport of swimming that has been galvanised by his success. The theory is, “If a local boy can do it, there is no reason that we can’t also do it.” It’s a very exciting time.”

Schoolings medal will be remembered fondly in isolation as a historic first gold for Singapore but also as part of a collection of strategies and programme implementations known as “Vision 2030” with the tagline “Living better through sport”.

“That is not for sport, but through sport,” Toh says. “The objective is to live better and that means different things for different people. We want more medals and more Joseph Schoolings but not just medals for medals’ sake. Accolades need to inspire people to live a better life, to be healthier, to bring communities together and to break down social boundaries. We largely judge our success as an organisation by how many young people are inspired to take up sport for the first time.”

With such a small population, the SSI can’t afford to lose any athlete that enters the talent pipeline. Of course leaks occur as young people lose interest along the way or incur injuries that permanently put them out of action, but unlike larger countries, every loss is keenly felt. That is why the SSI places great emphasis on retaining every athlete in the system as they advance up the pyramid.

“We can’t rely on mere numbers,” Toh admits. “We have to work doubly hard in both talent identification as well as talent retention. That is why in 2016 we established a national youth sports institute to ensure each promising young athlete has the necessary support in terms of access to the latest sports science and medicine as well as management and psychological needs. No stone can be left unturned because if we suffer leakage, we are in trouble down the line.”

A key strategy in swelling the base of the pyramid lies in the creation, and the subsequent championing, of sporting heroes that young people can look to and wish to emulate. The SSI worked closely with Schooling and his family in the aftermath of his historic gold and the sport of swimming has seen a dramatic increase in participation.

“With a European sounding name and an ancestry that is Caucasian, many Singaporeans were unsure whether or not Joseph was a true blue national,” Toh says. “He is third generation and when he or his wonderful family walk the streets of Singapore he is a symbol for us all.

“The creation of heroes depends on more than just success. It depends on the individual, on the sport and on how much the nation connects with the athlete’s story. We push our athletes to be conscious that they are competing for more than personal glory. Joseph has bought into this message from the first day he represented our nation in the pool.”

This cohesive sporting identity ties in with the advantages that being a small nation provides. Toh takes inspiration from Iceland’s remarkable run at last year’s European Championships that saw the tiny Arctic island knock out England in the round of 16.

“We have not been in touch with Iceland’s football association but we certainly cheered them on!” Toh beams, hinting at a kindred spirit shared with the diminutive European island nation. “Here in Singapore, we’re not just small in terms of population but also in terms of land mass. That means that we can coordinate all our efforts in our national stadium and that no one is ever more than half an hour away from assistance or evaluation and most importantly of all, we can concentrate our resources on a select number of athletes and they can fully buy in to our mission and our vision.”

The SSI works closely with the Department of Education and conducts talent identification tests on 10% of the cohort they are interested in over two weekends in a central talent hub. With all the nation’s top youth athletes assembled so closely together, different sports associations communicate with each other and facilitate a fluid ethos that might see a young athlete move between codes. This way, athletic potential merely shifts from one code to another rather than dissipate entirely.

“We can’t be too picky which sports our young people choose to pursue and we have to be vigilant of the changing landscape,” Toh says, pointing out that one of the fastest growing sports on the island is ultimate Frisbee. “The Olympic movement has shown itself to be open to new sports and you just never know what the next big event is going to be. We’re guided by our youth, not the other way around.”

Having said that, Toh admits that, like any nation, Singapore places a higher value on particular sports. Events that are included in the South East Asian Games and the Summer Olympics receive the majority of financial and operational support.

Resources are finite and space is a premium on the congested island. As Toh says, “Sometimes we have to make a call and one of the 40 to 60 associations that we support is left unhappy. That is the nature of any managerial job.”

All of these variables have to be navigated alongside a vital pillar of Vision 2030 and that is the continuation of Singapore being seen as a truly great sporting destination. Formula 1, the World Rugby Sevens, the BNP Paribus Women’s Tennis Association Finals all call Singapore home and, according to Toh, have all enhanced the nation’s reputation as well as enthusiasm from the masses.

“We’re punching above our weight in terms of hosting events that are of interest around the world but it is simply one piece of the puzzle,” Toh explains. “As I said, our vision is to live better through sport. For some people that might be watching the best tennis players, for some it might be being inspired to pick up an oval ball after watching the rugby sevens and for others it might be pursuing gold after watching Joseph. Either way, we’re living better through sport.”

Toh’s dream of seeing Singapore mix it with the giants of world sport by 2030 may be an optimistic one, but his organisation is certainly making all the right waves. If everything clicks into place, and the tiny island nation can create a culture where young athletes not only play host to the world but also cross oceans to conquer it, Joseph Schooling’s achievements could be remembered as just the first splash.