9 September 2016

A Tsunami of Dominance: The Unstoppable Force of USA SwimminG

Daniel Gallan

Every year, new teams are crowned champions over a wide spectrum of sports, but there are only a handful that will forever echo throughout eternity as conquerors. The Brazilian footballers of the 1960s, the West Indian cricketers of the 1970s and ‘80s, the current New Zealand All Blacks who dominate rugby union; these reigns, as mighty as they appear, pale in comparison to an empire that stretches back to the very beginning. USA Swimming has exerted a stranglehold on their sport since the first Olympic Games and haven’t let go since. Thanks to a dominant mindset, they won’t be letting go any time soon.

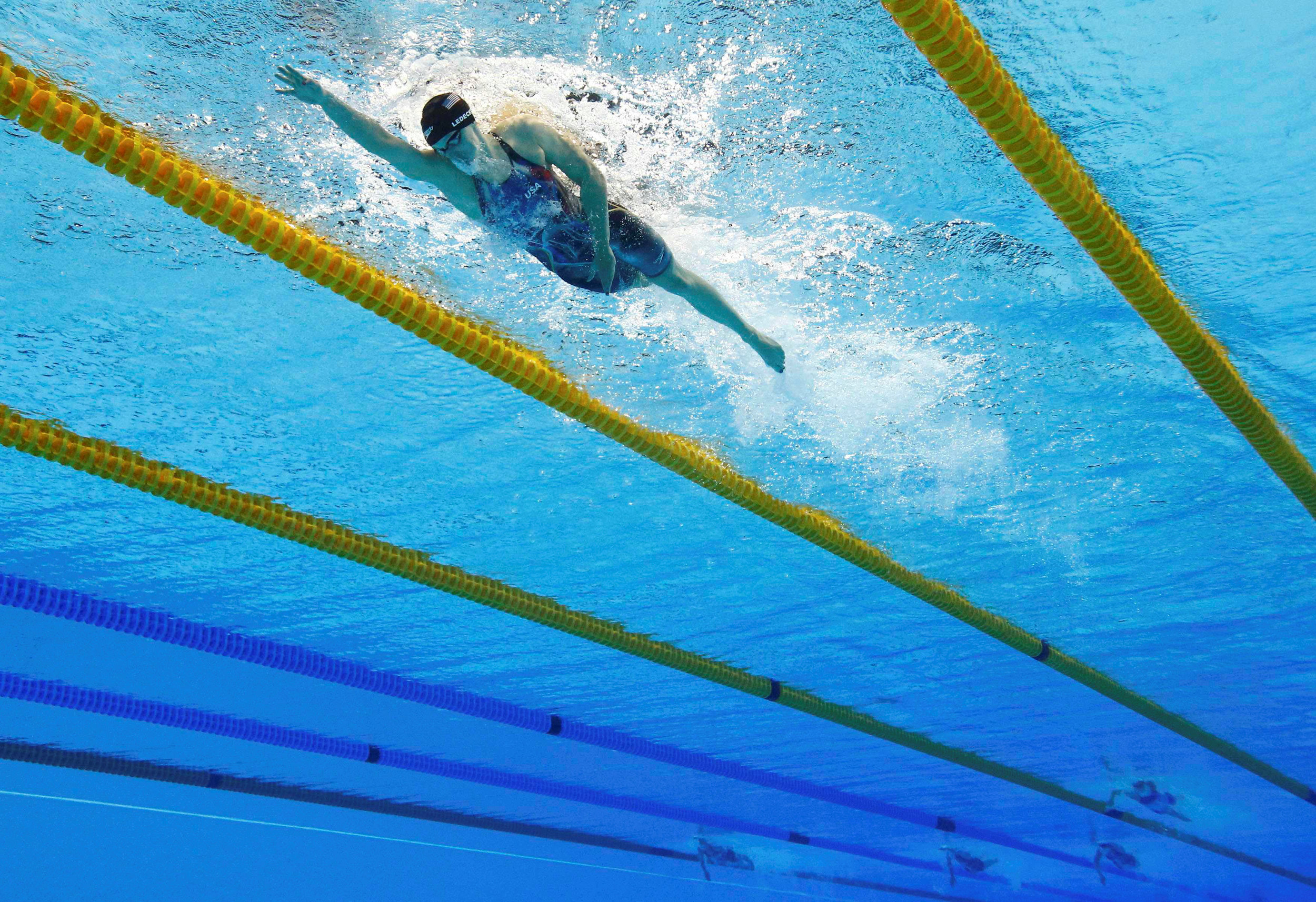

Katie Ledecky of USA Swimming steams ahead of the competition in the women's 800m freestyle final at the Olympic Aquatics Stadium in Rio de Janeiro. As this photo demonstrates, the gulf between the USA and the rest of the competition is vast. Image supplied by Action Images / Stefan Wermuth.

If looks could kill, South Africa’s most decorated Olympic swimmer, Chad le Clos, would have left this mortal realm on Monday 8 August 2016 minutes before the men’s 200 butterfly semi-final. Le Clos, in a bizarre attempt to psych himself up before the race, was shadow boxing right in front of his main rival and the favourite for the event, Michael Phelps. As this video clearly demonstrates, Phelps was not impressed.

The friction between these two athletes dates back to the London 2012 Games when le Clos won gold in the 200m butterfly by beating Phelps, the two time defending Olympic champion and world record holder, by 0.05 seconds. It was one of the greatest upsets in Olympic history and one wondered whether or not the best days of Phelps were behind him.

That loss and the shadow boxing provocation four years later was all the motivation Phelps needed to prove any detractors wrong as he went on to win his 20th Olympic gold medal (he would finish the Games with 23 to go along with 3 silver and 2 bronze). The image of le Clos looking helplessly on as Phelps motored ahead of him in the next lane added an extra talking point to the narrative. After touching the wall, Phelps raised his index finger, affirming his status as the number one swimmer in the world. Le Clos’ antics did little more than stoke Phelps’ fire as he finished out of the medals in 4th place.

All the best teams in the world throughout history have carried an aura that translates onto their field of play. The great Brazilian football team of Pele, Garrincha and Jairzinho of the late 1950s to the 1970s dominated the game with a freedom and flair that represented the people and spirit of their nation. Likewise, the all-conquering West Indian cricket team of the 1980s played the game with an aggressive and free-flowing style that challenged the traditional white rule of the sport. Their dominance was used as a galvanising force in the Caribbean and is still regarded as a metaphor for the culture of the islands that they represented.

The same union of ideology and athletic implementation could be used to describe USA Swimming and the stranglehold they have over the rest of the world. Like Phelps, the rest of the team relentlessly strive to be the best and are not afraid to let everyone else know it.

Lilly King, gold medallist in the 4x100m medley relay and 100m breaststroke, caused a ripple of controversy when she wagged her finger at her Russian competitor and alleged doper, Yulia Efimova. Critics argued that King was being arrogant, but the 19 year old brushed it off by saying, “I’m not this sweet little girl, that’s not who I am.”

King and Phelps are just two of the 47 swimmers who represented the USA in Rio but they perhaps best represent the overarching philosophy of the team. USA swimmers exude an aura of expected dominance. Of course, hard work, sacrifice, talent and dedication all play a major role in touching the wall before anyone else, but this team is ingrained with a desire to win that permeates throughout the organisation.

Lindsay Mintenko, National Team Managing Director of USA Swimming sums it up when she says, “We are the best in the world because we continuously strive to be the best in the world. There is no compromise. Every swimmer on our team has earned their right to be there based on their performance at Trials and once they're part of the team, we believe they are all going to win medals.”

Since the first Olympic Games in 1896, American swimmers have won a third of all medals. Of the 557 gold medals that have been handed out, 45% of them have been won by Americans. That dominance continued in Rio with American swimmers winning 16 out of 35 golds and 33 out of 104 combined medals.

What is more remarkable is that Americans only accounted for 5% of all swimmers in Rio. Clearly this is not an army of orcs that rely on their sheer weight of numbers to bring home glory. Granted they were the largest swimming team in Rio, but each member of the team was of the highest calibre.

So what is the answer then? Why is the USA so dominant? According Mintenko the success of the team can be heavily attributed to a unified and winning culture. “We have such strong leaders within the team, and even though most people view swimming as an individual sport, we make sure that everyone is pulling in the same direction,” she says.

Lilly King wags her finger in Rio. Some might argue that her actions were arrogant, but this ingrained sense of expected dominance has carried USA Swimming to heights no other team can reach.

Mintenko knows that it takes a team effort to drive individuals forward. In 2000 she was part of the gold-medal winning 4x200m freestyle relay team in Sydney and repeated that success in Athens four years later where she also won silver in the 4x100m freestyle relay. “I don’t attribute any individual medals to anyone else besides those who won them, but I know that a winning team culture plays a massive role.”

Two of the three female team captains for USA Swimming did not medal in Rio. Despite a lack of individual success, Mintenko was full of praise for Camille Adams and Elizabeth Beisel for rallying their troops and helping some of the younger swimmers, referencing the way they were always available to offer advice or help with an athlete’s preparation.

“They were amazing,” Mintenko says. “They really captured the spirit of the team. Sure, they didn’t perform in the pool as well as they wanted to, but I know that they are so proud to have captained a team that exceeded all expectations.”

Before the Games, USA Swimming had set themselves a target of 26 medals. The United States Olympic Committee (USOC) demanded 30. “We absolutely exceeded those expectations,” Mintenko gushes proudly. “But as soon as we got together post Games we wanted to deconstruct the success.”

This is a difficult thing to do, especially when expectations were so comprehensively surpassed. Mintenko points out that certain developments in strength and conditioning as well as nutrition since London 2012 has improved performances in the pool. She also references the impact the NCAA system has had on breeding swimming talent around the country with elite coaches and swimmers coming through its ranks, but from an outsider’s perspective, that doesn’t quite explain this dominance.

Once a swimmer is selected to represent the USA, they are made to feel like part of a family. “What truly sets us apart from the rest of the world, and I know this for a fact, is that we are truly a team,” Mintenko says. “Michael [Phelps] and Katie [Ledecky, who won 4 golds and 1 silver in Rio] might be standout performers, but they do not receive any more attention or help than any of our other swimmers. Everyone is made to feel like we believe they can win gold.”

This flies in the face of conventional resource allocation methods in elite Olympic teams. In a previous article, Finbarr Kirwan, High Performance Director at USOC, admitted that certain sports federations receive more funding and resources based on their chances of bringing back gold medals. Time and energy are not infinite resources, even for the behemoth that is USA Swimming, and by this logic, swimmers like Phelps and Ledecky should be receiving the lion’s share. This is not the case.

“Our philosophy is that the best way to motivate our athletes is to treat them all the same,” Mintenko says. “That motivates the top swimmers to prove their class and it shows the swimmers who might not necessarily win medals that they have been selected because we believe in them. Our coaches pull all the talent out of them and our ethos drives motivation.”

This age of dominance shows no signs of stopping. Michael Phelps may have retired but with a crop of young superstars making waves in Rio such as Ledecky (19), Lilly King (19), Ryan Murphy (21), Simone Manuel (20) and Caeleb Dressel (20), the future appears to be paved with gold.

“The key thing for us, and for the next generation of young swimmers, is to stay hungry,” Mintenko says. “We have to be hungry in our search for that extra piece of technology or innovative training methods that will see us improve. The things we did in Rio weren’t around in Beijing and we don’t know what will be available in Tokyo. But if we want to continue to be the best we have to be open to everything.”

That philosophy divides the good from the great. There is not an ounce of complacency to be found in USA Swimming. There is an expected dominance that is not founded on entitlement but rather an innate knowledge that no stone has been left unturned in the pursuit of excellence.

This can manifest itself in an overtly hostile way, as was seen in the Ryan Lochte scandal, but the fine line between arrogance and self-assured confidence is often crossed, and which great team in history has been without moments of indignity?

If the rest of the world hopes to catch up, perhaps there needs to be a change in mindset. Australia, Hungary, Japan, Great Britain, China and a host of other nations would dearly love to close the gap and challenge the USA. Thanks to the psychological hold team USA has on the sport, that does not look likely to happen any time soon.

CONQA Sport is hosting our second annual Elite Sport Summit in Cape Town on 5 & 6 October 2016.